A kind of book review. Elske Rosenfeld, 2021

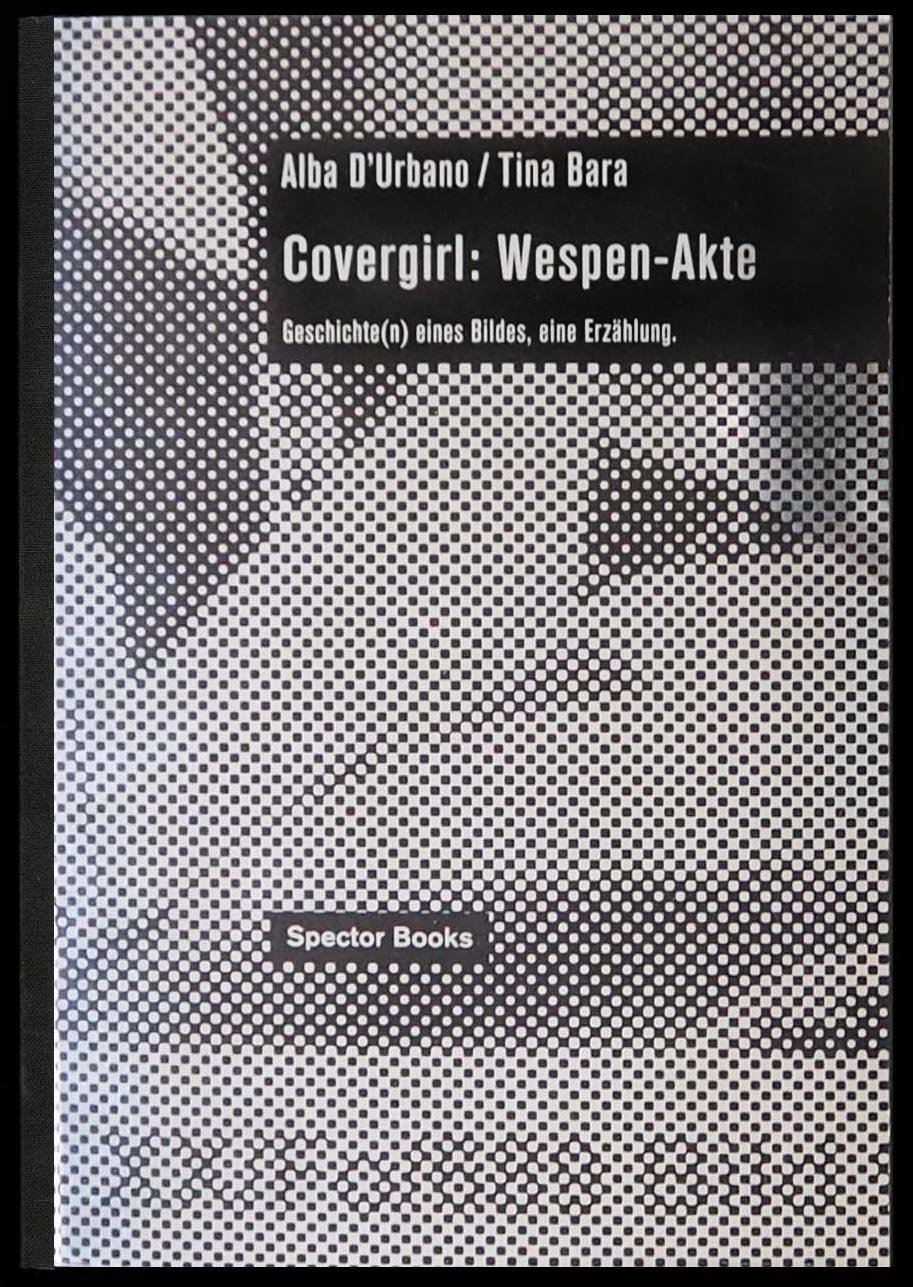

Covergirl: Wasp Files. History and stories of an image, a narrative (Spector Books, 2016) is about a series of encounters and entanglements between a number of biographies, images, and works of art. It documents and completes the eponymous project Leipzig-based artist Alba D’Urbano and photographer Tina Bara developed between 2007 and 2016 in response to a set of artworks and publications by an internationally active conceptual artist. The artist is named in the book, but will be referred to here as XX. The point here is not to call out an individual, nor is the scope of the book confined to the specifics of this case. Its contribution lies in the questions it raises about how processes of appropriation, abstraction, and (de)contextualisation can come into play when historical materials, especially from underhistoricised or underrepresented contexts, are valorised into works of “critical art”.

During a residency for international artists in Leipzig in 2007, XX conducted research into images held by the East German state security service Stasi. In the resulting exhibition at the Galerie für Zeitgenössische Kunst (GfZK), a video showing a fictionalised meeting between a Stasi informant and their case officer was accompanied by several series of ready-mades: photographs found in the files of, among others, a group of women, captured sunbathing and chatting together in the nude. Unbeknownst to XX, one of the women was Tina Bara, a photographer and professor at the Academy of Fine Arts Leipzig, a stone’s throw from the GfZK. Covergirl’s story begins in 2007 just after the closing of the show, when Bara finds herself, superficially “anonymised” with a black bar across her eyes, on the cover of XX’s exhibition catalogue, which her colleague D’Urbano had brought back from the gallery to their shared offices.

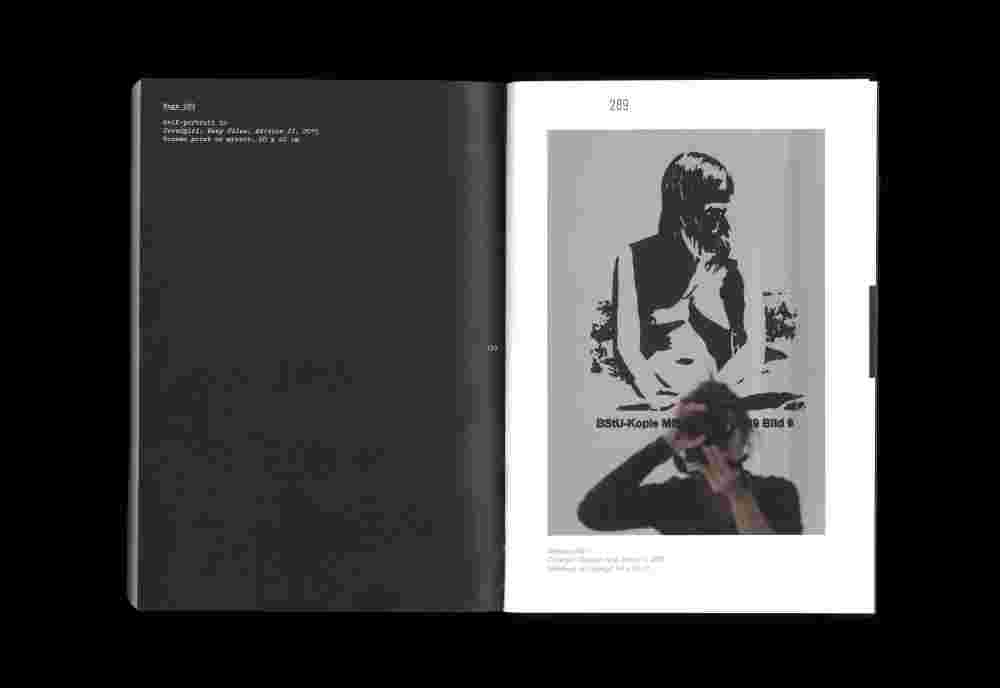

Covergirl documents the series of appropriations and re-appropriations that transported the nude photo of Bara and others from the particular, historical context of the 1980s GDR’s dissident cultures via its regime of mass-surveillance and its historicisation into the space of contemporary international critical and commercial art. With the support of D’Urbano, Bara traces the images back to a weekend excursion of members of a women’s anti-militarisation group, Frauen für den Frieden [FfF, engl. Women for Peace] in the mid-80ies, where they had been taken by her friend and fellow activist Katja Havemann. They ended up in the hands of the Stasi during a raid at another of the women’s homes. In 1990 the “wasp files” (“wasps” was the Stasi’s codename for the group) passed into the custodianship of the Stasi Records Agency (BstU), an institution set up to preserve and provide access to files for victims and researchers. The images were discovered there by XX during her research; who would then them on display in her Leipzig show, sell them as art prints, and use one of them – Bara’s naked image – on the cover of her catalogue. XX decided not to seek or include further information on the images’ context of origin or their passage into the hands of the Stasi, nor to try and ascertain the identity and whereabouts of those portrayed. She mislabels the series: “Women, naturist meeting, end of the seventies”. Her e-flux announcement describes the work’s artistic merit like this: “The material here presented out of its historical context reveals itself surprisingly, as a peculiar form of narrative: conceptually highly interesting examinations of human behaviour and gestures that at times call to mind the Theatre of the Absurd.”

D’Urbano and Bara’s book is based around a reversal of XX’s decontextualising and abstracting move: it reconnects the catchy catalogue cover back to the historical constellations of intimacy, resistance, and repression from which it was lifted in order to be valorised as art. A trail of correspondence of Bara with the Stasi Records Agency as well as with the XX maps the ethical and legal grounds and the professional and institutional motivations that guided the image’s transit across contexts and times. But the two artist’s project does not aim at or exhaust itself in this reconstruction, nor in passing moral judgment on the ethics of XX’s work. The book and the art works it documents elaborate their own, different approaches to the nexus of history, biography, image politics, and aesthetics engaged by the images’ transposition into art. Felix Guattari and Suely Rolnik among others have used the term ethico-aesthetic to show the two, ethics and aesthetics, to be intrinsically linked. In XX’s and the Covergirl project such constellations are made, often around quite similar formal aspects, in vastly different ways. It is through their juxtaposition that the book broaches valuable questions about the ethical and aesthetical economies that elevate documents of past violence into objects of value in the circuits of contemporary “critical art”. I will go over a few of them here:

De/Re-contextualisation: In XX’s work artistic value is produced through the decontextualisation of the images, freeing them up for the artist’s formal and conceptual play and skilful inter-textual referencing (“conceptual examinations”, “theatre of the absurd”). But to understand the ethico-aesthetics of such a move in the image’s concrete case, this de-contextualisation must itself be contextualised:

An international art audience may or may not be aware that East German perspectives were at the time of the work’s presentation largely absent, not just in the international field of art, but also in German mainstream discourse itself. A German Gedenkpolitik [commemoration politics] that passed its historical judgment in binary vocabularies inherited from the Cold War, had invisibiled lives lived in degrees of acquiescence and resistance to a repressive regime. Blanket condemnations of all things Stasi had foreclosed a discussion in which some form of accountability or reconciliation might have been achieved. It was in this space of absences and open wounds that XX lifted her as yet historically unprocessed materials, as decontextualized footage into the international field of contemporary art.

D’Urbano and Bara’s works, take precisely the opposite path, of re-contextualising or, in fact, creating a context for the readability of the images in their historical, political significance. In the absence of public discourse, contemporary art can and often has become a proxy space: people come to art to assure themselves of their otherwise invisible past. The video Re-Action and the photo tableaus of Story Tales (both from 2008-2009) can provide such a space for its protagonists and audiences: In both, D’Urbano and Bara revisit the women portrayed in the series of nudes, returning the images to the women, and the women into the images.

Figurations of Other/ Self are part of this re-appropriationand are engaged, once again, differently here and in XX’s work. The latter skilfully fine-tunes the exact degree of otherness/exoticism and abstraction (“naturist meeting”) that make the women’s bodies maximally available for the free play of the desires (conceptual, formal, sexual) of the both, her the creator, and the consumers of her work.

By contrast, D’Urbano and Bara’s works reinvests these bodies with personhood in ways that can be expected to challenge, rather than service the expectations of international art audiences (possibly even in welcome ways). The project’s strength also lies in how the two women bring their different and constantly shifting degrees of proximity and distance to the images and their story to bear: It is clear that D’Urbano needs Bara, and Bara needs D’Urbano to make this work.Where XX construes the material and its personnel as “other” to an unmarked, “neutral” artists’ or art viewers’ self, D’Urbano and Bara address their respective otherness to or entanglement in that materials throughout – as that which enables and conditions their dialogical approach.

The question why XX’s othering failed to raise any alarms in an art world that has thankfully become more sensitized to the violence of such acts is interesting in itself. It is clear however, that the point of D’Urbano and Bara’s intervention is not to say that histories should only be owned and worked on by those directly affected by them. In Covergirl it is precisely the collaboration between the two artists – the absorption in and processing of her past of the one, the witnessing and sorting through of the other – that makes their interventions work.

Anonymisation/ the black bar/XX contributes to the othering performed by XX’s work. Her picture series does not addresses the black line she dutifully applied to all faces: it remains an unwelcome, but necessary blip in the picture – a response, as minimal as possible to legal requirement, spilling its (presumably) unintentional associations of criminality, illegality, or obscenity onto its depersonalized subjects. In a later, bizarre and unpleasant twist of the story the letters “XX” will take on a similar function in an artist book by XX. Here the two letters will anonymise Bara’s beautiful and heartfelt letters to her, which she reprints here, again, without Bara’s knowledge or consent. To the naked body of subject that does not speak, XX adds speech that has no author-body. When Bara confronts her with this renewed transgression, the XX explains that she did not seek permission, because she had worried that Bara would not grant it. Well, yes…

D’Urbano and Bara, by contrast, make the black bar into another site of formal and contextual analysis in the Covergirl works. Their video and print series Re-Flection (2010-2011)play with the aesthetics and mechanics of the black line, including its use by the Stasi Records Agency (who permitted the use of the pictures on the condition that they be anonymised this way) and in XX’s work. When the black bar slips from Bara’s face to her crotch (or rather, to the crotch of a life-size photo of a naked female body on one of D’Urbanos “skin dresses” which Bara wears), the work adds an interrogation of the naked female body in art history, porn, its shaming and disciplining.

These and the other works of the Covergirl project show, that attention to a work’s ethics and to the context in which it unfolds, does not have to come at the expense of its aesthetic effectiveness. That, on the contrary, artistic value can be made there: where historical, relational sensitivity deepens and expands a work’s formal, aesthetic richness and complexity.

When XX deploys Bara’s nakedness on her book’s cover, all we learn is what we may have already feared: that what works for the most opportunistic realms of advertising still works to sell a book as critical art. D’Urbano and Bara decided to put Bara’s picture on their cover, too. But when we squint at it, to make out a figure among the bitmap of black dots on a reflective ground, what we catch sight of is mostly ourselves.